This story was originally published by Injustice Watch, a nonprofit newsroom based in Chicago. Subscribe to Injustice Watch’s newsletter here.

CHICAGO — Public defenders are often depicted on TV as bungling, overworked, and uncaring. But that didn’t stop Sharone Mitchell Jr. from wanting to join the Cook County public defender’s office after graduating from the DePaul University College of Law in 2009. While being a public defender might not seem like glamorous work, he found it fulfilling.

“I got the opportunity to go in court and represent people who may have had the worst day of their lives,” Mitchell said. “And if we didn’t get ourselves involved, that worst decision of their lives would follow them for the rest of their lives.”

In March, Cook County Board President Toni Preckwinkle selected Mitchell to replace former public defender Amy Campanelli. It marked a return to the office for Mitchell, who served as an assistant public defender from 2010 to 2016. Before rejoining the office, Mitchell was director of the Illinois Justice Project, a nonprofit policy and advocacy group. He played a prominent role in the successful fight to eliminate cash bail, working with dozens of community organizations and lawmakers who pushed for the historic criminal justice reform bill that passed the Illinois legislature in January.

Mitchell said he wants to use his new position to make the case that a more powerful public defender’s office is just as important to structural change in the criminal justice system as ending cash bail or reducing the police department’s budget.

The stakes are high. Public defenders play a critical role in the criminal court system by representing clients who can’t afford a private attorney — about four out of every five defendants in the Cook County Circuit Court, according to Campanelli. The vast majority of the public defender’s clients are Black and Latinx, reflecting a court system that disproportionately prosecutes people of color.

But the public defender’s office has struggled to attain the same level of visibility — and funding — as its opposition across the courtroom: the state’s attorney’s office. Mitchell said that power and resource imbalance reflects a system that has relied on punishment and incarceration, rather than focusing on fixing the root causes of poverty, crime, and violence.

“I think that the public defender’s office and our community partners stand for the proposition that this system has not worked, [and] that this overreliance on incarceration has not kept us safe,” he said.

Mitchell said a better-funded public defender’s office with a seat at the proverbial table could be a leader in the fight for equity and justice.

Public defenders “put a mirror to the system and say that this isn’t working for us,” Mitchell said.

Public Perception And Visibility

Mitchell grew up in South Shore and West Pullman, two predominantly Black neighborhoods on Chicago’s South Side. Where he grew up, he said, he “didn’t have the prerequisite pigment to believe” that the criminal justice system was about good people holding bad people accountable.

He remembers falling in love with the legal profession as a sixth grader in a mock courtroom at Metcalfe Community Academy in West Pullman, when he was chosen to defend his fellow classmates.

He first worked at the public defender’s office in 2007 as an intern and then joined as a trial attorney three years later. There were times, he said, when it seemed like everyone was against him.

Mitchell recalls many clients who became frustrated after he told them that they faced the option of pleading guilty to the charges against them or risking longer sentences if they decided to fight their case and lost. Judges and prosecutors thought public defenders were slowing down the system when they mounted a vigorous defense for their clients, he said.

But the negative perception of public defenders long predated Mitchell.

In 1988, Randolph Stone became the first Black person to lead the Cook County public defender’s office. At the time, the office was seen as lacking independence, Stone said. The head of the office was appointed by the chief judge of the Cook County Circuit Court and individual public defenders were approved by judges. Clients complained that public defenders weren’t representing them well, Stone said.

One of Stone’s initiatives was to make the office’s work more visible to the public. He wrote a biweekly column in the Chicago Defender, encouraged his assistant public defenders to take on speaking engagements with community groups, and advocated for criminal justice reforms.

“By being public, by collaborating with others, by being in the community, you’re able to foster that positive image and let the public know the positive things you’re doing,” Stone said.

Later, he helped push for legislation that gave the Cook County board president the power to name the public defender, creating a level of independence from the judiciary, he said.

Stone, who left the office in July 1991 to become the director of the University of Chicago’s Mandel Legal Aid Clinic, said the public defender “needs to be a hero, not only for individual clients but also for reform.”

Campanelli operated under a similar philosophy. During her tenure from 2015 to 2021, she increased the office’s visibility by speaking on panels about sentencing reform, sitting on government commissions focused on reducing reliance on incarceration for children and young adults, and using her public profile to talk about inequities in the criminal justice system. Last year, she filed a lawsuit against the Illinois Department of Children and Family Services over its blanket ban on supervised visits during the Covid-19 pandemic and filed a court motion for the mass release of jail detainees at the beginning of the pandemic.

“I think one of the great things we saw out of the previous administration is that Amy Campanelli was willing to be heard. And she was willing to be a part of the conversation,” Mitchell said.

Like Campanelli and Stone, Mitchell said he plans to make the case directly to the public that his office has an important role to play in pushing for criminal justice reform. But he’ll also have to fight for increased resources for his office.

The Fight For Budget Parity

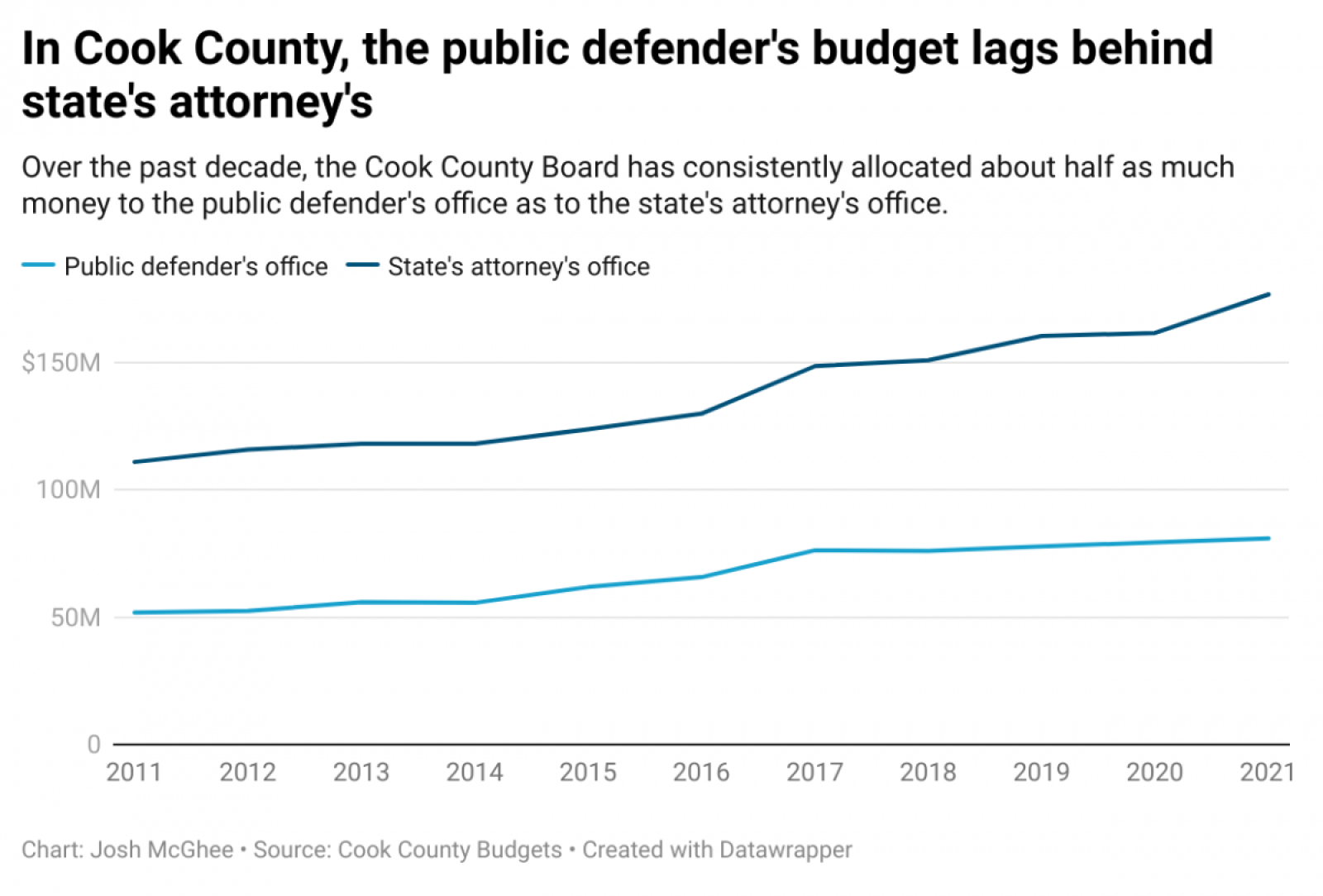

Cook County spends far more on prosecuting criminal cases than it does on public defense. That budget disparity is common in large justice systems, and it means that public defenders have large caseloads and spend less time on each client, which leads to worse outcomes for defendants, according to research.

A 2020 study from the University of Illinois at Chicago’s Institute for Research on Race and Public Policy found that in U.S. counties in which public defenders and support staff have larger caseloads, defendants are more likely to be detained pretrial. In counties with smaller caseloads for support staff, felony defendants received shorter sentences. (The study comprised 11 large, urban U.S. counties, not including Cook County.)

The Cook County state’s attorney’s office had a budget of $176 million in fiscal year 2021, compared to the public defender’s budget of about $80 million. In addition to the general funds that it receives from Cook County, the state’s attorney’s budget includes money that it receives through forfeitures and $39 million in federal, state, and private grants. The public defender’s office hasn’t raised a million dollars in grants in any year in the last decade, according to an analysis of county budgets by Injustice Watch.

The two offices have different functions, missions, and needs, which account for the budget disparities, Preckwinkle said in an emailed statement.

Cook County State’s Attorney Kim Foxx — who said she sees Mitchell as an “ally” in criminal justice reform work — said part of the funding disparity is explained by the role that the state’s attorney’s office plays outside the criminal courtroom, including defending the county against civil lawsuits.

Any comparison of the two offices’ budgets has to take into account differences in the scope of their work, she said. But she agreed that the public defender’s office should be well resourced.

When attorneys are overburdened or overwhelmed, it takes a toll on their clients, Foxx said. “If you don’t have an attorney who is giving you their full attention, able to do the necessary research … you’re not getting effective counsel,” she said.

Over the past decade, the public defender’s budget has consistently been around half of the state’s attorney’s budget.

Andrew Davies, a criminologist at Southern Methodist University who researches indigent legal services, said the overall budget may even understate the true disparity because police do a lot of legwork in investigating cases before giving them to prosecutors, while public defenders have to pay investigators out of their own budgets.

“Resource-wise, [prosecutors] are in a position to outgun the defense every time,” Davies said.

The lack of adequate resources can make it difficult for public defenders’ offices to retain quality attorneys, said Patrice James, the co-founder of the Black Public Defender Association, a national organization aimed at improving defense for low-income people.

“People [are] no longer being able to sustain themselves in the work,” James said.

This dynamic might be playing out in Cook County. There are currently 38 vacancies out of more than 400 attorney positions in the public defender’s office, according to Mitchell. The attorneys who are left have to do more with less, facing a felony case backlog that has grown more than 20% since the start of the pandemic.

Looking ahead

Even as Mitchell faces many of the same challenges as his predecessors, he is optimistic about his new role. He sees opportunity in a slew of reform legislation that passed the state legislature this year, including the bill ending cash bail that he helped pass in January.

“This bill, by increasing the likelihood somebody is going to be released, will allow us to do our jobs better, get cases to trial, and win trials,” he said.

The Illinois General Assembly also passed a bill Monday that will allow a new immigration unit in the public defender’s office that Campanelli launched last year to represent clients facing deportation in immigration court.

Hena Mansori, the unit’s supervisor, will now be able to hire two attorneys this year to begin to address a long-standing problem: The majority of people in Chicago immigration court last year did not have an attorney to represent them. This unit will help “expand the scope of the public defender’s office,” Mitchell said.

Mitchell also hopes to hire more investigators, interpreters, case workers, legal secretaries, paralegals, and administrative assistants to support the attorneys’ work and provide “holistic representation,” he said.

That means not only representing clients in court but also “being in connection with people that may be going through a crisis by providing those folks with things that they need to make life a little bit easier to ensure folks aren’t returning to the system,” Mitchell said.

Ultimately, Mitchell said, his goal is to provide the best representation possible in the courtroom and work with advocates and organizers pushing for systemic change.

“There are things that we can do in the courtroom as public defenders, but I think that our overall impact is capped if we’re just thinking about what we’re doing in the courtroom,” he said. “We have to pair that work with folks who are doing the work outside to help change the entire structure that we’re operating in.”